Myths about Prison Labour

This section is all about the myths used to justify the use of prison labour and the expansion of the prison industrial complex.

Prison Labour helps to normalise work

The Government’s ‘working prisons’ policy stated its’ aim to get prisoners working up to 40 hours a week. This is impossible to deliver when cuts are ensuring less staff and longer bang up for prisoners. A ‘working week’ is not achievable with the staff shortages and staff cuts the state are imposing. The scarcity of work in the prison means it is used as a privilege and incentive to control the prison population.

The Government’s ‘working prisons’ policy stated its’ aim to get prisoners working up to 40 hours a week. This is impossible to deliver when cuts are ensuring less staff and longer bang up for prisoners. A ‘working week’ is not achievable with the staff shortages and staff cuts the state are imposing. The scarcity of work in the prison means it is used as a privilege and incentive to control the prison population.

There is nothing ‘normal’ about being a worker in jail; where you have no choice, autonomy or control over the means of production. Research has shown that work in prison – which is monotonous and tedious – does nothing to make work on the outside appealing or pleasurable. If anything it highlights why its easier and more rewarding to accumulate wealth through crime rather than through wage slavery.

Researcher Jenna Pandeli, writes how ex-prisoners with low skills are less likely to find employment upon release, firstly, as these low skilled jobs are moving abroad and secondly because ironically they are moving into prisons.[1] She also writes about the alleged skills prisoners are meant to gain: “The findings suggest that prisoners are not, for the most part, taught a transferrable skill within the orange-collar workshops. Arguably, the only skill they obtain is the capacity to complete boring and monotonous work (or develop strategies to cope with boredom and monotony).”

The main reasons people work in jail are so that they can earn money to buy phone credit and essentials on canteen (as most people do not have people that can send them money), or to simply get out of their cell. It is an opportunity for social interaction to help people survive their sentences. It doesn’t contribute in any meaningful way to ‘rehabilitation’.

Prison Labour is Education

Doing ‘education’ in jail, in terms of it being your main employment, is generally paid less than other jobs. Therefore people will actively opt-out of doing courses that could develop their literacy for example to earn more in prison workshops. Most work in prisons is repetitive, low skilled and not related to developing a useful trade. While many people do gain an education in prison, such as Open University degrees, this is generally achieved in spite of the prison service, not because of it. It’s a tragedy that education only becomes an option when locked in a prison, rather than in the community. People should be fighting to save education and develop educational alternatives on the outside and asking why people are only accessing education on a prison sentence.

Doing ‘education’ in jail, in terms of it being your main employment, is generally paid less than other jobs. Therefore people will actively opt-out of doing courses that could develop their literacy for example to earn more in prison workshops. Most work in prisons is repetitive, low skilled and not related to developing a useful trade. While many people do gain an education in prison, such as Open University degrees, this is generally achieved in spite of the prison service, not because of it. It’s a tragedy that education only becomes an option when locked in a prison, rather than in the community. People should be fighting to save education and develop educational alternatives on the outside and asking why people are only accessing education on a prison sentence.

Where people are achieving qualifications, such as NVQs, these are often related to industries that are in decline, such as manufacturing. Then comes the simple fact that people come out to a culture of work that fellow workers face – zero hour contracts, minimum wages that are impossible to live on, poor working conditions, workplace stress and so forth. Ex-prisoners will then be at the bottom of the hierarchy of a mass of unemployed people.

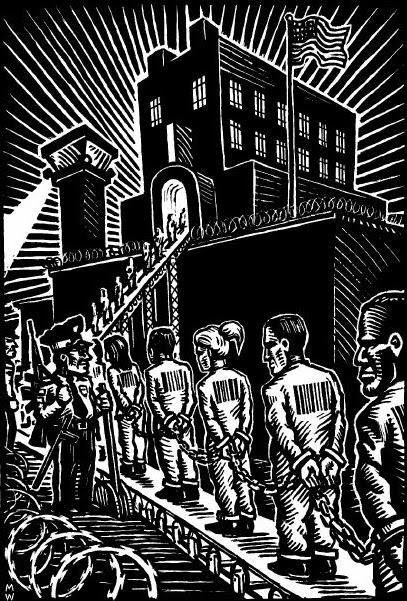

Prison Labour is important for Rehabilitation

Prison labour historically began as a way to occupy prisoners. They were given ‘hard labour’ with pointless tasks like breaking rocks or turning tread wheels. It then became clear that prison labour could serve the interests of capitalists and those in power more explicitly. World War I and II was propelled by prison labour, and in recent times the invasion of Iraq was made viable by the prison economy of the United States. Prison labour is responsive to the market and the national economy and now more than ever is creating a dangerous precedent that is slowly building an economy based on caging human beings.

Prison labour historically began as a way to occupy prisoners. They were given ‘hard labour’ with pointless tasks like breaking rocks or turning tread wheels. It then became clear that prison labour could serve the interests of capitalists and those in power more explicitly. World War I and II was propelled by prison labour, and in recent times the invasion of Iraq was made viable by the prison economy of the United States. Prison labour is responsive to the market and the national economy and now more than ever is creating a dangerous precedent that is slowly building an economy based on caging human beings.

Prison is not about rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is the liberal discourse used to rationalise imprisonment. There is zero evidence about the prisons ability to ‘rehabilitate’ and the concept of rehabilitation is a grey area. Is there a ‘model citizen’ we want prisoners to become? Do we want them to be functional for the economy as consumers and producers? Prisons do not offer healing. They are more likely to hinder any attempts for people to live the lives they want, due to their disruptive nature and traumatic impact on people and their families.

In addition, a large number of the prisoner workforce are lifers and long termers who are not going to be ‘rehabilitated’ or re-introduced into society any time soon. It is actually these long-termers that prison industry employers prefer. Likewise, a lot of people working in prison workshops are those that are more likely to have better literacy or numeracy skills as jobs are banded on security levels, and a lot of jobs will exclude drug users for example. Therefore the people with the most complex needs remain subjected to the worst jobs, or no jobs (and periods in segregation and on basic).

The core logic of modern prison governance is economic, Crewe[2] writes how, “One part of this framework is a more forceful insistence on the financial accountability and frugality of government institutions. Imprisonment should be cheap, cost-effective and able to justify itself to a parsimonious public…According to this logic, it should also learn from commercial practices or have its functions contracted out to the private sector if viable and economical.”

Prison labour is about profit. It is about people accumulating wealth off the exploitation of others. It is not about care or desire to help people.

Prison Labour has no effect, or relationship to Labour ‘Outside’

Prison labour in the United States was a direct response to the increasing control and power of unions. Prisoner workforces present a win-win for companies; not only are labour costs significantly reduced, but there are no rights of employees; no sick pay, no paternity leave, no trade union legislation, for example. By the nature of the prison system, workers are able to be controlled through discipline and punishment more easily, and are ultimately disposable and replaceable by the consistent supply of prison labour.

Prison labour in the United States was a direct response to the increasing control and power of unions. Prisoner workforces present a win-win for companies; not only are labour costs significantly reduced, but there are no rights of employees; no sick pay, no paternity leave, no trade union legislation, for example. By the nature of the prison system, workers are able to be controlled through discipline and punishment more easily, and are ultimately disposable and replaceable by the consistent supply of prison labour.

Prison industries take jobs directly away from communities on the outside. One example of this is the tool company, Speedy Hire who sacked more than 800 workers and closed 75 depots in 2010. In the year 2010-11 however it increased its prison contract by almost ten percent paying Erlestoke, Garth and Pentonville prisons £114,012 for the services of almost 100 prisoners. Countless other companies have done the same. The director of another company, Calpac, said they wouldn’t even be able to afford to pay people the minimum wage.[3]

Prison labour has been a tool to break strikes of outside workers, or respond to the strength of industrial unions by simply bringing work into prisons, where prisoners cannot organise. Neoliberal free trade capitalism has moved manufacturing and other industries abroad. With increasing unionising, workplace organising and the growing power of social movements in the Global South, prisons present a solution to growing labour unrest worldwide. This is why solidarity with incarcerated workers is completely essential.

Likewise, as Garvey[4] states ‘once punishment becomes a source of profit to the state its incentive to punish increases’. Is this the kind of society we want to live in?

For more information about the Prison Industrial complex, click here.

References

1. Orange-Collar Workers: An Ethnographic Study of Modern Prison Labour and the Involvement of Private Firms, By Jenna Pandeli, August 2015, Management, Employment and Organisation Section of Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University.

2. Crewe B. (2009) The Prisoner Society: Power, Adaptation and Social Life in an English Prison. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

3. http://www.exaronews.com/articles/4335/companies-hire-slave-labour-at-uk-prisons

4. Garvey, S.P. (1998) Freeing Prisoners’ Labour. Stanford Law Review, Vol. 50, pp. 339- 398.